Creating a pocket wifi portal

My pocket wifi hard at work changing minds and educating the masses as I zoom through the California countryside

A few months ago, I stumbled across this zine from Iffy Books, a Philidelphia bookstore with a focus on hacking and free culture. The zine detailed a simple way to make a tiny captive portal - the ‘click here to connect to WiFi’ screens when you connect to a public network. The concept immediately appealed to me - a non-obtrusive, simple way to broadcast whatever message you’re trying to spread to any number of strangers who happen to be around you. I went to Amazon and bought a couple boards for just a few dollars, and then promptly let them collect dust at my desk for months.

However, that summer, I enrolled in ITP Summer Camp, a mixed media arts program that I vowed to use as the catalyst for finally finishing at least one of my never-ending list of side projects. To further cement this commitment, I volunteered to lead one of the camp workshops to teach others how to make their own pocket WiFi portal (despite not yet finishing my own). With a new, self-imposed three-week timeline before the workshop, I got to work.

Hardware

Setting up the hardware was a breeze with the use of the Iffy Books zine. I downloaded the Arduino IDE, ran the example programs, and was up and running in no time. There’s a recommended plugin, SPIFFS, which I made great use of. It allows you to upload an entire directory to the chip instead of manually typing in stringified HTML into the Arduino editor.

Two hardware limitations really shaped the development of this project. The first was that since this device obviously couldn’t connect to the Internet, everything on the website I made would need to be local. No CDNs, no Google Fonts, no links to outside resources. And the second was that the tiny ESP8266 chip could only hold up to 4 MB of information. In an age where a TODO list app’s node-modules folder rarely measures under 1 GB, this requirement was a throwback to the internet of the 2000s, where every byte mattered.

The Website

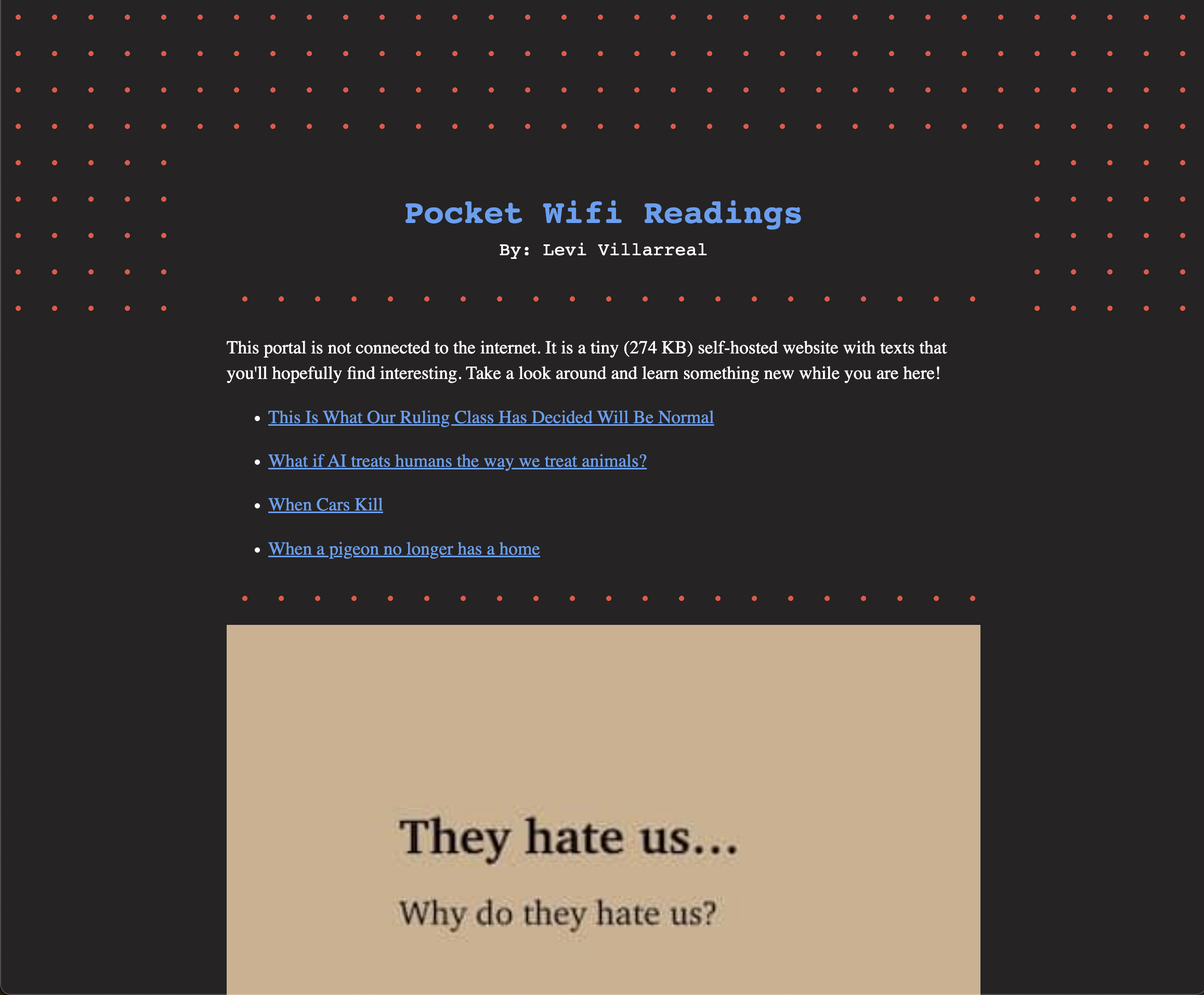

Working within these limitations had its own kind of charm. Constrained as I was, there were still many avenues of creativity to explore and play with. Hosting anything like a video documentary or anything with many images was off the table. And since the website needed to be entirely static, I couldn’t make anything that used an actual backend, such as a collaborative experience between multiple WiFi access point users (I want to explore this further in the future). I eventually settled on hosting a few articles that pertained to causes I cared about.

I spent a few hours just reading through old and new articles. I eventually settled on 3:

- This Is What Our Ruling Class Has Decided Will Be Normal Published by Crimethinc.

- What if AI treats humans the way we treat animals? Written by Marina Bolotnikova

- When Cars Kill Written by Danyoung Kim

- And an illustrated slideshow I stumbled across on TikTok late one night that made me tear up every time I went back to it

These articles touched on three topics I cared deeply about and already talked about at length with the people in my life. Animal rights, Palestinian Libration and an immediate Gaza ceasefire, and the scourge of cars in American cities. They are all causes I had physically attended protests/rallies for on multiple occasions, and I wish to see more people become aware of them. And convince others to become politically or socially active themselves for these causes.

I took my first pass at constructing a website to host these three articles and 12 images. I wrote the site with no frameworks, no preprocessors, just straight HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. After a decade of using a double-digit number of hip new web technologies, it was satisfying to go back to basics. I settled on a design that has remained unchanged since (inspired by Matt Bateman): simple, unassuming, and reflective of your dark/light mode preference.

Screenshot of the tiny website homepage

What did undergo multiple iterations, though, was the loading speed of the site. In initial testing, the captive portal was noticeably slow to load, even though the site was less than 2MB. Testing the portal on an airplane with many people connecting made it nearly impossible to get the site to load under 30 seconds. I made many optimizations to bring this time down. I replaced the custom-loaded font face in favor of the system available Courier, ran the twelve images through compression algorithms, and, crucially - condensed all the CSS, HTML, and JS files into a single file. All of these improvements reduced the website’s size to a miniscule 274 Kilobytes. This drastically improved load times and greatly reduced the strain on the tiny chip (not to mention scoring a 100 on Lighthouse for performance).

Chip Case

In one of the sessions at ITP camp, we explored using Womp, an opinionated online 3D software tool. I hastily designed a 3D enclosure and printed it on the school printers. That night, I ran around the studio trying to find whatever free adhesives I could to glue the enclosure together. I used a mix of super glue, rubber cement, and stickers to attach the lid to the case, stuffing the box with scraps of fabric from the sewing station so the chip would not rattle around inside.

Render of the 3d enclosure

While the final look definitely has a vibe that I love, I would recommend a better enclosure. It’s painfully obvious that this is far from my best CAD work, but the STL files are in the repo root if the reader wants to try their best at replicating this enclosure.

The final enclosure - completely covered by ITP camp stickers. As seen from the Coast Starlight Amtrak observation car

Workshop

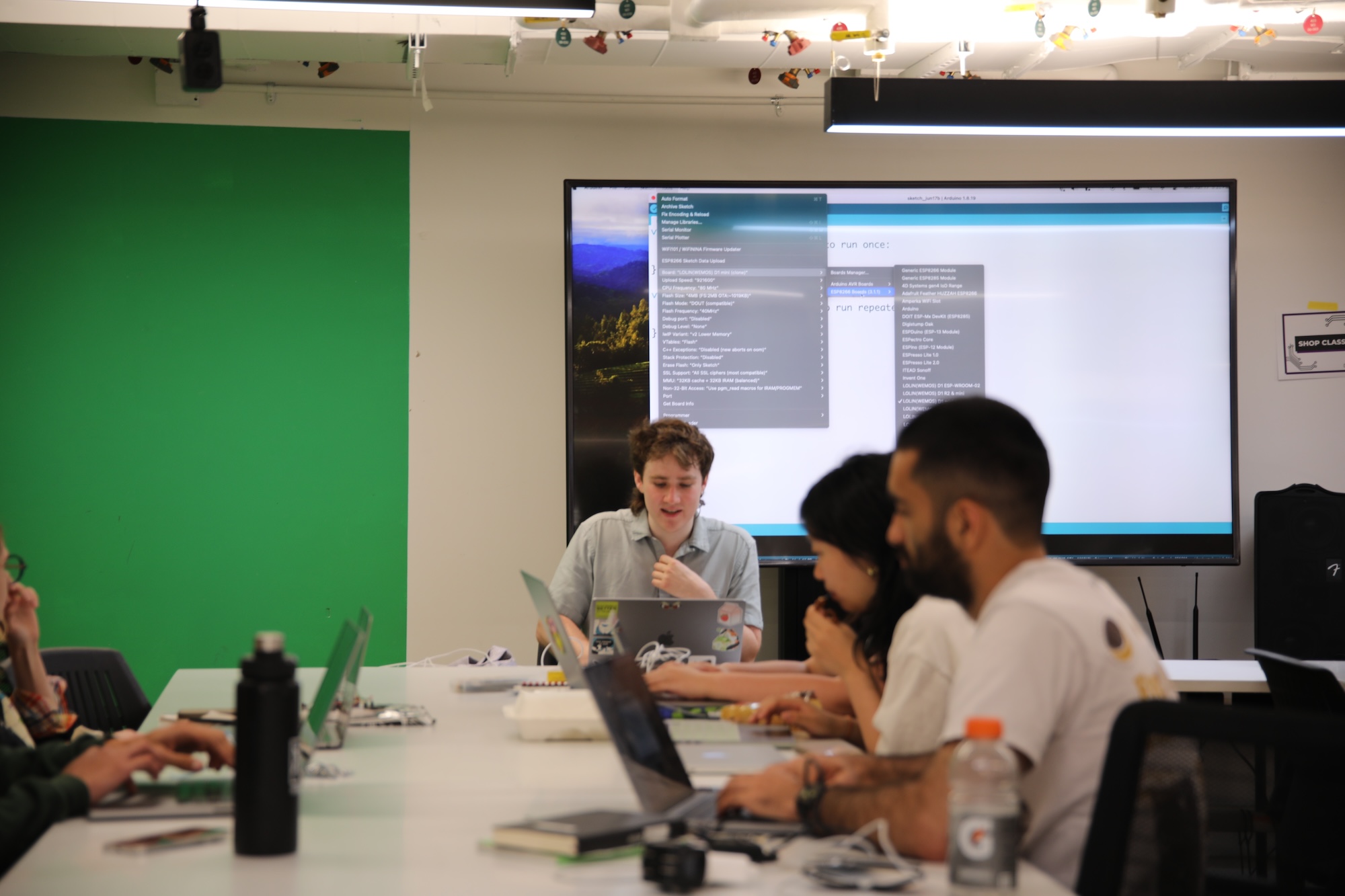

Coming full circle - I still had to lead the ITP workshop to share what I learned. The day before, I had been invited to my friends’ last-minute NYC City Hall wedding and subsequent Brooklyn Bridge Park photoshoot. Fully aware of the close timing - I left a bit early and sped off on a Citi bike through the streets of downtown brooklyn on a 90+ degree summer day. Showing up only a minute late - I led the workshop to a class of ~20 people - sweat stains and all. I brought many more boards (USB-C this time!) and led the class through installation and setup. We left with a host of new networks vying for attention in the WiFi tab of any unsuspecting ITP camper.

Action shot from the workshop

Reception

For about a month or so - I kept this pocket wifi on me at all times, powering it on the train, planes, or when I was at confrerences. I also kept one at my desk at work plugged in 24/7. I’ve found that captive audiences are the best - especially planes. If you’re in a situation where you have no data, and hours of free time on your hand, chances are you’ll see if by some miracle the airline you’re flying offers free WiFi, entertainment, or at least an interactive flight map. Flights were when the network was by far the busiest, and at the beginning of a flight, I could often look over to my fellow passengers phones and see them looking at the home screen of my pocket wifi portal. Since there’s no easy way that I know of to easy log visits or analytics, the exact number of people is a mystery - but if at least one random internet surfer read an artcile and had a perspective change, I’ll call this project a resounding success.