Stem Cells and Gene Editing A Cure for Type 1 Diabetes — Exploravision

Type 1 diabetes in an autoimmune disorder that affects as many as three million Americans, and millions more around the world. Once diagnosed, you are sentenced to a lifetime of checking glucose levels and diet monitoring. While many advancements have been made in the past few years when it comes to treating type one diabetes, many of them focus on making it easier to live with it, rather than eliminating it entirely.

For the 2017 exploravision competition, our team at Waxahachie Global High School: Saika Brice, Alex Mercado, Maccoy Merrell, and Levi Villarreal set to propose a theoretical cure to type one diabetes. We researched the cause, and failed cures of type one diabetes, and came up with a viable solution to the autoimmune disorder. None of this research would be possible without the help of our teacher and mentor, Mrs. Restivo, who originally encouraged us to pursue this project.

Background

Type 1 diabetes is a disease in which the body produces little to no insulin on its own, rendering the body unable to regulate blood glucose levels. Current treatment options involve monitoring glucose levels and injecting the required dosage of insulin. People with type 1 diabetes must constantly track their blood sugar levels, often with glucometers to coordinate their treatment plan with their lifestyle.

The Cure

Our solution for curing type 1 diabetes involves a two-step process that will solve the underlying problem associated with the autoimmune disease. The first step involves creating insulin-producing beta cells from lab-grown stem cells. In the human pancreas, islets contain alpha, beta, and delta cells that work together to regulate blood sugar. The function of the beta cell is to sense glucose and release necessary amounts of insulin to allow the sugar to enter the cell. In type 1 diabetes, there are few or no beta cells to produce insulin, which creates a buildup of glucose in the blood, depriving the body of its main source of energy.

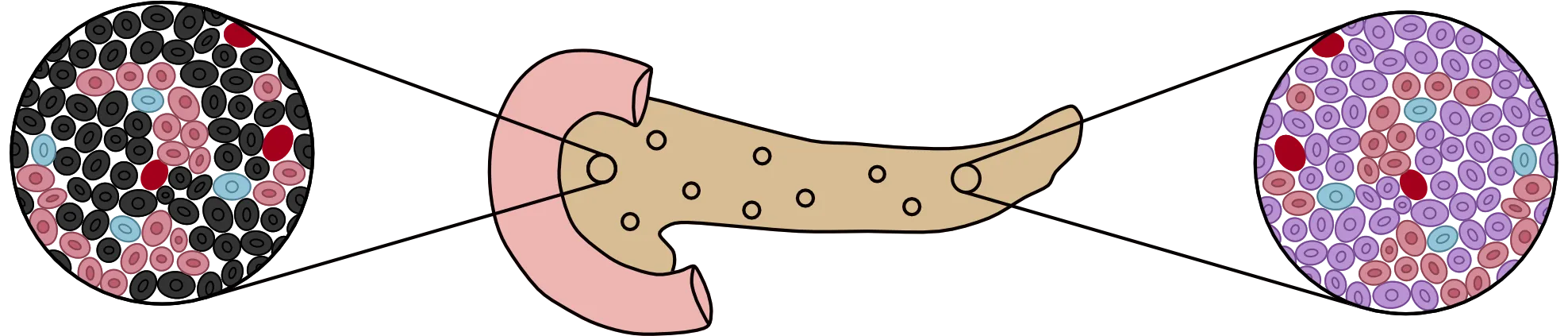

Diagram showing the death of beta cells (black) in an unhealthy islet versus healthy beta cells (purple) in a healthy islet

Due to recent advancements in beta cell understanding, scientists have discovered that beta cells are destroyed at an early age in type 1 diabetics. Research headed by Decio L. Eizirik, Izortze Santin and their team have found that beta cells have anti-virus receptors that recognize and treat viral infection within the cell. In rare circumstances, however, susceptible beta cells do not withstand the attack of a viral infection, especially in young children, which leaves fragments of the virus embedded in the beta cell itself. When the immune system senses these viral fragments, it triggers an excessive reaction. The immune system kills the cell and identifies other beta cells as threats, continuing to attack until there are little to none left in the islets.

Considering the nature of the immune system’s response to these insulin-producing cells, the only viable option to restore complete function in the pancreas would be to introduce new beta cells into the body. This theory has seen mild success with donated pancreata from cadavers. However, that solution can still lead to the immune system identifying the cells as foreign and rejecting them from the pancreas. A more viable solution involves growing the beta cells from stem cells collected from the patient’s own body to ensure the highest probability of success.

Pluripotent stem cells can give rise to several different cell types, including beta cells. By harvesting and growing pluripotent stem cells from patients, the eliminated beta cells can be replaced. Using a multi-step process involving both internal and external signals, these undifferentiated stem cells can give rise to hundreds of thousands of functioning, healthy beta cells. Using this in vivo differentiation has already shown positive results in tests involving rats and has a feasible chance of working just as well in humans.

A graphical representation of stem cells

The second step of the process to cure type 1 diabetes involves creating the protein PD- L1 and attaching it to the membrane of the beta cells. Although stem cells provide the opportunity to reintroduce healthy beta cells to the body, T-cells in the immune system still pose a threat. T-cells are a type of white blood cell that produces cytokines to help eliminate harmful viruses. In a normal immune system, the T-cells can recognize and destroy foreign, harmful, or cancerous cells. However, in type 1 diabetics, autoaggressive T-cells invade the islets and focus on the destruction of the beta cells.

To prevent this response from T-cells, our solution proposes the use of the protein Programmed Death-Ligand 1, more commonly known as PD-L1. PD-L1 is a transmembrane protein and spans the entirety of the cell’s membrane, functioning as a gateway to permit the transport of specific substances across the biological membrane. This protein corresponds with Programmed Death 1 (PD-1), which is found on the surface of T-cells. Due to the strong affinity between the two proteins, PD-L1 binds to its receptor, PD-1, delivering a signal that inhibits the release of cytokine, which is used to attack cells perceived as threats by white blood cells. This interaction suppresses the immune system and allows the cell to evade detection. If used on the membrane of differentiated beta cells, it would block their destruction and prevent the cells from being perceived as a threat.

To implement the protein PD-L1 into the lipid layer of a beta cell, a new type of genome editing technique called CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) could be utilized, greatly reducing both the cost and time of the gene editing process. The specific DNA sequenced from a cell that produces PD-L1 naturally could be injected into the beta cell using the CRISPR/Cas9 approach. This would grant the beta cell the ability to produce PD-L1 on its own. After these beta cells are fully prepped, a radiologist can use ultrasound and radiography to guide a catheter to the portal vein of the liver, infusing the beta cells through the tube.

Breakthroughs Needed

For our solution to be viable, breakthroughs would be needed in stem cell harvesting, genome editing, and CRISPR technology.

A process perfected by the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard Stem Cell Institute involves incubating embryonic stem cells and introducing a variety of internal and external signals, resulting in beta cells at the end of the three to four-month process. However, the use of embryonic stem cells is often seen as unethical, and these cells can often be in short supply. To combat these problems, scientists have reverted adult stem cells to embryonic stem cells with limited success, opening another avenue for advancement. The method starts with isolating a normal adult cell, such as a skin cell. The cell is then introduced to an acidic environment, stressing it until it reverts to an embryonic stem cell-like state. As the process is refined, it will become more efficient and allow mass beta cell production without the constraints facing embryonic stem cell research today.

In addition to refining the process of stem cell production, advancements must also be made in the realm of stem cell differentiation. Currently, the factors that are involved in stem cell differentiation are not completely understood, and the process takes ample amounts of time and money to see results. To optimize beta cell production, the process must be streamlined, and a methodical, efficient approach must be found. However, once the method is developed, introducing the beta cells into the body involves another set of challenges.

Scientists have isolated the protein PD-L1, which is used to identify and target diseased cells. Properly utilizing the protein will protect the beta cells from T-cell attacks. Few methods currently exist to utilize PD-L1, which will need to be embedded within the phospholipid bilayer of the beta cell. Advancements in genetic alteration could potentially yield a solution, as CRISPR has the potential for precise genetic engineering. Currently, stem cells trials only have a 4% success rate, but enhanced methods of utilizing CRISPR will yield better results. Successfully altering the genome of beta cells to produce the enzyme and treat it as a surface protein would yield a significant advancement in the medical field. Although the introduction of CRISPR-altered beta cells would potentially cure diabetes, using the treatment on humans would require intensive trial testing. While the technology is quickly becoming a reality, it might take several years before there are any large-scale trials of CRISPR.

To utilize the protein PD-L1, CRISPR will need to encode new codons within the cell. The trials to test the ability for the cell to produce and utilize the protein will be the last step in producing a cure for type 1 diabetes. To grant beta cells immunity against attacks, scientists will need to introduce Cas9, a CRISPR protein, to the newly produced cells. Scientists will then need to supply the Cas9 protein with schematics, instructing which loci of the DNA to target (Reis et al., 2014). Once located, the protein will insert the codons that are required to produce programmed death ligand one (PD-L1). While typically only seen in pregnant women, PD-L1 has the potential to be used as an immune system suppressant. Once the codons for producing the protein have been transcribed, the cell will then need to replicate the protein readily, treating it as a necessary part of its systems. The new proteins will then need to be transported near the plasma membrane of the cell, or be carried outside the cell’s membrane. When various macrophages encounter the cell, the protein will bind to its receptors, preventing it from destroying the beta cell. After such trials, the beta cells will show resistance to the immune system.

The technologies required to effectively treat and cure diabetes are being utilized more than ever before. Labs have successfully produced stem cells from adults with the potential to produce beta cells from a reliable and abundant source. Bioengineering has advanced to the point where genes can be identified, located, and altered. The breakthroughs required to develop such technologies are complex, but not impossible. Once these obstacles are overcome, diabetes will be cured.

Consequences

Those affected most by this technology would be type 1 diabetics themselves. Because this solution solves the underlying problem of type 1 diabetes, there would no longer be a need to continue insulin treatment. This alone would save diabetics thousands of dollars a year in treatment, and prevent countless needle pricks, injections and carbohydrate counting. In addition to the financial benefits, the symptoms associated with type 1 diabetes, including excessive urination, weight loss, and blurry vision, would be eliminated.

The curing of type 1 diabetes would also have significant benefits in the world of autoimmune diseases. The use of the protein PD-L1 would set a precedent as an effective immune system suppressant, making it a viable treatment for diseases such as multiple sclerosis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. However, there are potential drawbacks from using PD-L1.

Because PD-L1 is often used by cancer cells to evade detection, new treatment is under development that specifically targets and destroys the protein (Sheng et al., 2016). This would be problematic for a type 1 diabetic whose resistance to type 1 diabetes is dependent upon the function of the PD-L1 protein. Despite the potential drawbacks, the positive implications of a diabetes-free future far outweigh the negatives.

Implications of this Research

Our team of students at Waxahachie Global High School was the first in years to take part in the Exploravision competition. After submitting our work to the Exploravision competition, we were notified that we had received an honorable mention from the organization, which was the first time, to our knowledge, that anyone in our district had received an award from this competition. Our awards were presented to us by our teacher Mrs. Restivo at the annual Waxahachie Global High School awards night.

From left to right: Maccoy Merrell, Alex Mercado, Saika Brice, Levi Villarreal

This project allowed all of the team members to learn about ways that type 1 diabetes is being studied right now, and propose our own solution to the difficult problem. We are excited to see which direction treatment technology will go, and hope that our solution could be beneficial to those researching such technologies.

To read the full results of our research, please read the full research paper with sources here