Systems thinking

This week I read a very engaging blog post that examined from a systems thinking perspective the protest of GMO crop experiments in the United Kingdom. Even though it was written in 2012, I really liked the approach.

I’m fascinated by the debate, because It seems to be a classic example of the principle of complementarity in action, with each group describing things in terms of different systems, and rejecting the others’ position because it makes no sense within their own worldview

This really drives home to me that systems thinking can often be understood as a practice of empathy, as what the author is really trying to do here is to understand where each side is coming from, and how they can both see themselves as just within their own worldview.

In examining my where my personal values lay within the systems the author enumerates, I find myself split between system 1 and system 6, while rejecting some of the systems outright, even if I can still understand the point of view.

I lean towards system 1 because I have historically been in favor of scientific advancement, and have seen the tremendous amount of good it has brought society on average in the past century. If reputable experts and ethic review boards have deemed that the potential upsides of the research is worth the risk, I tend to take them at their word. And especially in this case, when the research is about more resilient, higher yield crops, I had no immediate objection.

Secondly, I am leaning towards system 6 because I believe that the multitude of problems that animal agriculture poses is a far more urgent and relevant issue to food security than a study involving GMO crops. Animal agriculture is by far the largest and most wasteful use of land in our food systems, and results in pandemics, antibiotic resistance, massive CO2 emissions, deforestation, and pollution of local water and soil. In short, research money and effort would be much better spent figuring out ways to reduce meat consumption, if our goal is to build a robust, sustainable and equitable future.

I found system 3 and system 8 at odds with each other. System 8 posits that crop diversity is key in resiliency to the face of new threats, but system 3 argues that a genetically modified crop would be a contaminant that weakens fragile ecosystems. The author seeks to remedy this by explaining that GMO crops could be a bigger step change than the system could handle, but I left unconvinced that these two systems didn’t directly contradict each other.

And lastly, I reject the authors conclusion.

The knowledge gain from this one trial is too small to justify creating this level of societal conflict. I’m sure some of my colleague will label me anti-science for this position, but in fact, I would argue that my position here is strongly pro-science: an act of humility by scientists is far more likely to improve the level of trust that the public has in the scientific community. Proceeding with the trial puts public trust in scientists further at risk.

Just because a group of people doesn’t understand or agree with research that could help billions, does not mean that there is sufficient cause to stop research of this magnitude. In a world where scientific institutes are bound by budgets and time, Rothamsted did due diligence by publicizing all their findings, and leading a public education campaign. I think this kind of overreaching stakeholder alignment has gone too far in recent decades. Although this inclination is an understandable and just reaction to gross corporate and governmental overreach in the early 1900s, it has killed so many projects that would have directly benefitted my generation. Some examples include:

- Nuclear power plants

- High speed rail projects

- Affordable housing

- Etc.

While I think it is never a waste to identify and name the systems and stakeholders, not all systems should be given equal weight. We need to carefully consider the number of people affected, the expertise of those involved, and the price of inaction.

Systems thinking for Taxidermy

For Taxidermy, my assigned topic in my Critical Experiences class, it is also relevant to identify different potential stakeholders and what their perspectives might be. For this thought experiment I will define 3.

-

An economic system of people wanting to enjoy and appreciate animals

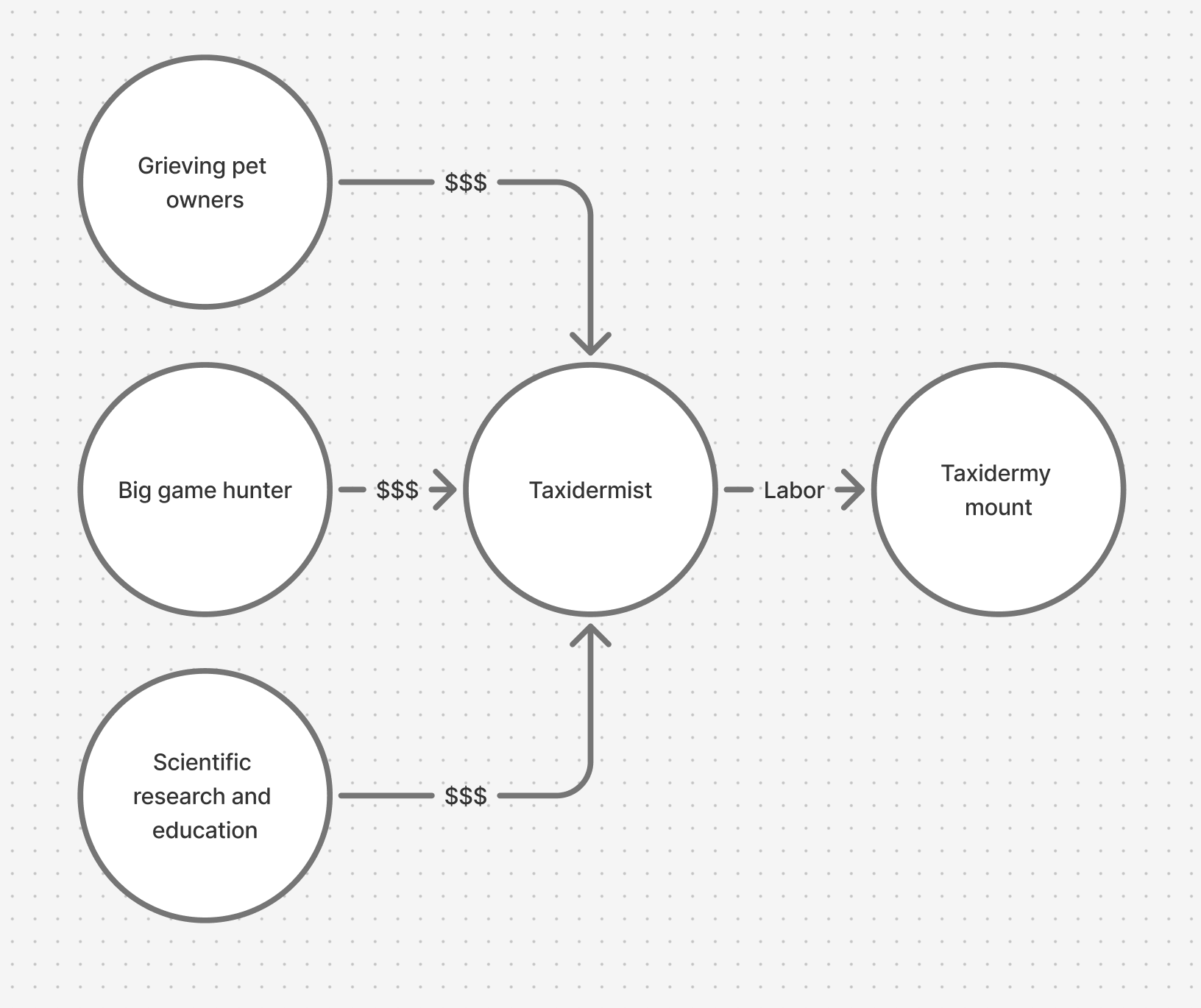

This system is the most easily digestible. Some people want taxidermy mounts, and are willing to pay for it. This could be for:

- Sentimental reasons: Memorializing a dead pet.

- Egotistical reasons: Big game hunters displaying their kills.

- Educational reasons: A museum wanting to use rare animals to entice and educate visitors.

At the other end of the system is someone who is willing to do the work of taxidermy in exchange for payment.

An illustration of the system map I described

-

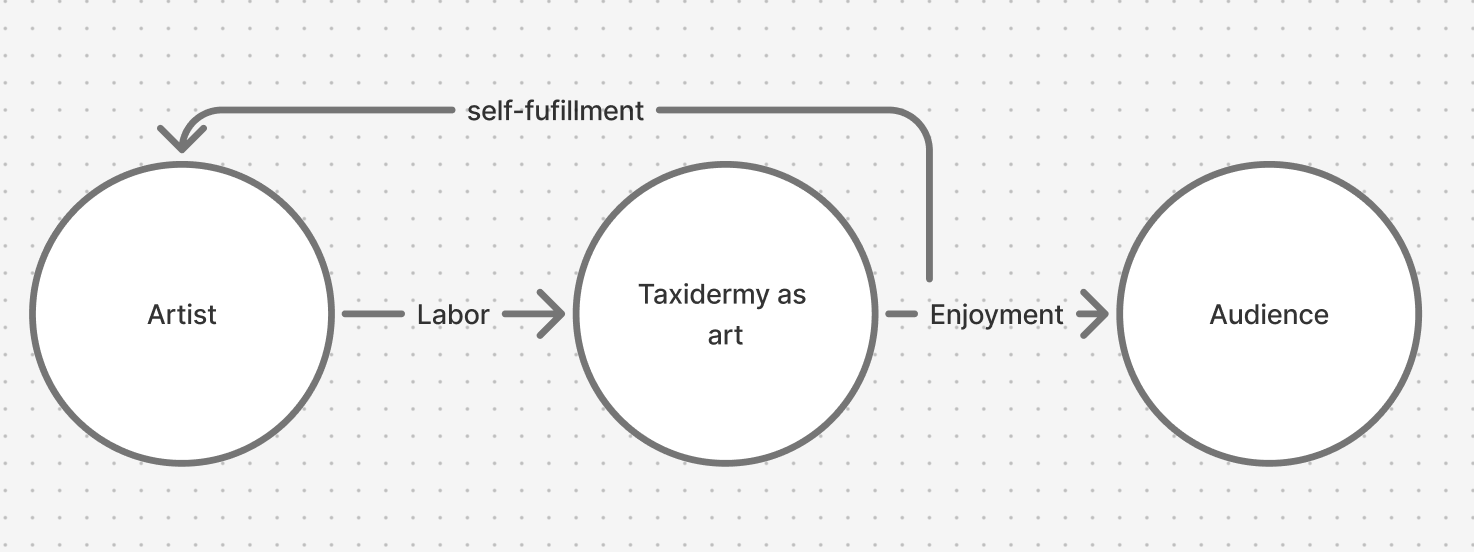

A system where taxidermy is valued for its artistic qualities

In this system, an artist may want to create a taxidermy mount for the personal satisfaction it may bring them, or for an intended effect it may have on an audience. In this system the taxidermies animal is a medium for conveying a message.

An illustration of the system map I described

-

A system of commodified animals for food and entertainment

This is the most complex system. This system is putting the animal as the main stakeholder and contextualizing them in the rest of human society. Animals exist within many systems in society that are almost entirely based around the pleasure of humans:

- Torturing and killing them for meat, eggs, dairy.

- Forced into cages for amusement at circuses or zoos.

- Companion animals chosen for their attractiveness and agreeability.

Within the context of these systems, taxidermy can be seen as another normalization of the commodification of animals for human taste and pleasure, even beyond the life of the animal. And while taxidermy does not necessarily require the killing of an animal before the end of its natural lifespan, it historically has, especially in the case of scientific studies and game hunting.